Alumni on the Move

Connectivity now: Why internet access in Africa is more vital than ever

The Covid-19 pandemic has had us grasping for silver bullets and easy answers. And while there is no ‘one thing’ that could solve this crisis, enabling greater connectivity should be number one on the to-do list. Why? Because connectivity is a catalyst.

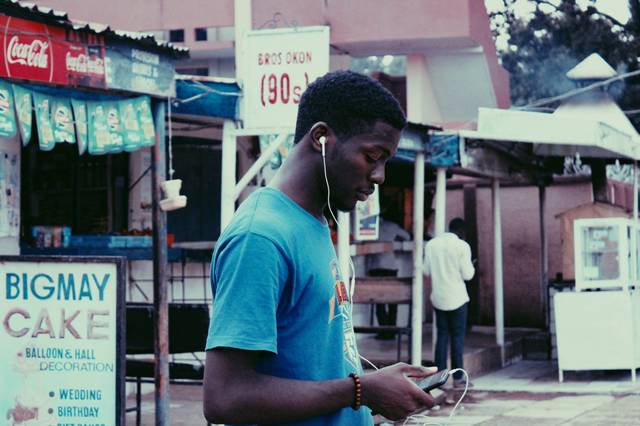

Internet access has been the ultimate source of technological “leapfrogging” in Africa. This explains why, for example, there are places without running water where one can stream a music video or make a mobile payment. But Africa is not nearly connected enough. It is still the continent with the lowest internet penetration rate at 39% of the population, compared to a global average of nearly 60%. What’s more, there are large differences in internet access between rural and urban areas, with smartphone usage in urban areas exceed that of rural areas by almost 200 per cent in some countries.

Covid-19 has shown the importance of connectivity. It has never been as important to share correct information and combat fake news, while being able to elicit information from citizens (and internet-users) on behaviour and movement.

Examples of the digital divide

South Africa’s effort to alleviate pressures on poor families is severely limited by connectivity, as applications for aid are submitted mainly via the internet. The only small businesses in operation during the harshest stages of the lockdown were those who are able to utilise the internet for essential deliveries or services. Even the South African Social Security Agency (SASSA) moved all its operations online, with its physical offices closed. Likewise, the divide between rich and poor schools in South Africa is made all the more pertinent by the fact that rich schools (some 25% of the total) are largely continuing their classes and giving assignments via the internet, while the poorest 75% of schools have been unable to do so and are at risk of not completing the academic year. Connectivity can also directly affects countries’ ability to fight the virus: Singapore and the USA, for example, have begun to use location tracking to identify who has been in contact with infected persons to enable isolation and Finland is using social media influencers to drive behavioural change.

Connectivity is good for democracy

The internet is a democratiser and aid to good governance; this explains why authoritarian governments always try to control it. In this time especially, when national emergency conditions might tempt governments towards overreach, the internet could help citizens mobilise and report irregularities. A 2019 global study by Guriev et al showed that the expansion of 3G networks decreased the public’s confidence in the national government while increasing the perception that the government is corrupt.

Why is Africa not more connected?

Having established that the internet could potentially be a ‘great leveller’, the question naturally follows: why is Africa not more connected?

The cause of Africa’s internet deficiency is, predictably, cost. Africa has the most expensive internet in the world. According to the Alliance for Affordable Internet, Africans pay on average 8,8% of their monthly income to purchase 1GB of data, compared to 3,6% in Latin America and 1,5% in Asia. In some cases, like Chad, the DRC and CAR, 1GB was found to cost as much as one-fifth of earnings. South Africa has the highest data cost among Africa’s 5 largest economies.

Price does not mean quality, as Africa is highly reliant on wireless internet to cover its vast spaces, sacrificing connection speed. Many African countries get by on download speeds of less than 1 Mbps – placing them in the bottom 8% globally in terms of internet quality and speed.

Big companies control the market, keeping prices high

Costs are high because service providers are largely unregulated and infrastructure is poor. In South Africa, a small number of companies control 70 per cent of the wireless broadband market, which has led to distortions in market prices. Market concentration in telecoms – a notable feature across the continent – is therefore largely responsible for our connectivity woes. The second reason relates to the first: because of poor or limited infrastructure for connectivity, there are large economies of scale for providers, which makes it more attractive to form monopolies or oligopolies.

The case for making the internet a public good

Meanwhile, there is an ongoing debate over whether the internet is classified as a public or a private good. The former, which includes streetlamps, public roads and breathable air, are goods that are ‘non-rivalrous’ (one person’s consumption does not diminish the total stock of the good), and non-excludable (there is no access control). Governments take responsibility for the provision of public goods, as there is no incentive for the private sector to do so (or if they do, they naturally form monopolies, like in the utilities or electricity business).

If we were to consider the internet a public good, it would naturally follow that government ought to provide it, as is the case in many European countries who are providing fibre and 5G broadband to their citizens. However, in Africa internet expansion has largely been driven by private companies.

Given the vast opportunities that Africa’s rapidly expanding population – at 1.3 billion today, projected to be 2.5 billion by 2050 – offer, it is not surprising that more private providers are stepping in. The mobile industry is projected to contribute $150 billion, or nearly 8 per cent of GDP across Sub Saharan Africa by 2022, up from $110 billion in 2017. New market entrants like Rain in South Africa (partly owned by Patrice Motsepe, Michael Jordaan and Paul Harris) promising a faster 5G network shows the power of disruptors on the sector.

The telecoms sector in Africa is entering into collaboration and competition with a number of other sectors, such as media, finance and retail, promising large returns. Telcoms are already competing with the finance sector by providing credit and insurance, by leveraging their access to customers’ spending data. Meanwhile banks are growing increasingly dependent on internet service providers for access to clients. However, private providers cannot move fast enough and will go where the largest returns are, thereby neglecting poorer areas where there is little to gain. This is why governments need to provide internet as a public good.

Great potential in key sectors

The internet could revolutionise agriculture and food security in Africa by giving smallholder farmers access to markets and finance. In the health sector, much of the internet’s potential remains untapped, with limited use of smart devices or remote diagnostics to date. But with Sub-Saharan Africa carrying 24 per cent of the global disease burden with just 2 per cent of doctors, this needs to change. Fixing access, pricing and infrastructure in the telecoms industry is perhaps as close to a silver bullet as African governments will come. That is if the impact of the internet in areas such as health, education and democracy over the past 20 years is any indication of its potential for disruption and growth in the future.

Benefits of connectivity can be reaped now

In South Africa, improving connectivity need not be a long-term goal. There are things that can be done today, for example by issuing more spectrum to data providers (as government has been directed to do by the Independent Communications Authority) to enable greater competition, and making 5G spectrum permanent. Learners in poor schools need internet access and tablets or smartphones in hand if they are to continue their school year.

Even if greater connectivity does not solve all our problems – from access to information and accountability to unemployment and poverty – simply attempting an improvement in South Africa will activate positive dividends.