Young African Magazine

The ubuntu we need: post covid-19 and beyond

What would happen if we put people first, and organised our societies and economies accordingly? Axolile Qina (South Africa & SU, 2016) shares a vision for an Ubuntu that goes far beyond embracing diversity. This Ubuntu would proactively prioritise human development through a leadership ideology that develops African countries, giving citizens the dignity they deserve and liberating all people on the African Continent.

The COVID-19 pandemic has denied us our daily social interactions with fellow human beings. It has caused a rift in our human interconnectedness, but technology has provided a way for us to remain human and continue to connect with one another through video calls, text messages and phone calls. The crisis has brought us together through technology, and we can utilise these technological advances to rethink how we conduct education, business and relationships. If the principle of Ubuntu is at the centre, a transformative system of economic development is possible through the prioritisation of agricultural development, the improvement of medical services and the creation of new approaches to education.

Introducing Ubuntu

Ubuntu is best captured in the isiZulu/isiXhosa expression, “umntu ngumtu ngabantu” (“a person is a person because of other persons”). Although this expression of Ubuntu is the most well-known, in Zimbabwe it is known as unhu. In the Shona language, it is expressed as follows: “munhu munhu nekuda kwevanhu.” These phrases function as a universal principle that expresses our common humanity. Ubuntu is embedded in a personhood that can only be fully comprehended in the context of community. In other Bantu language groups of Rwanda (Kinyarwanda), Burundi (Kirundi), Central Uganda (Luganda), and a collection of dialects in Western Uganda and Northern Tanzania (Runyakitara), ubuntu/obuntu is a general characteristic of generosity towards fellow humans and a sense of humanness towards the community.

In an article in the Journal of Business Ethics titled ‘Cultural Values, Economic Growth, and Development,’ Symphorien Ntibagiriwa, Coordinator at the Institute of Development and Economic Ethics (IDEE) in Bujumbura/Kigali, defines Ubuntu as “a moral character and value of people when they live, act, and behave in the way that fosters harmony in the society and the universe around them.” This universe is interrelated with the physical human community around us (family, friends and society), as well as the ‘unseen’ realm of ancestors and spirits. A person does not exist outside of the community, as they have the responsibility to identify with their immediate community of origins, often represented by their family and ancestors, and then conscientiously engage with other people in the wider societal community.

Leadership in uncertain times

How leaders have responded to the pandemic shows the extent to which Ubuntu is a principle in their attempts to develop and economically liberate their people. The crisis has exposed vulnerability and led to reactive behaviour by some leaders, responses that are fuelled by the uncertainty of not having control over this virus. There have been various responses from global leaders. Some have prioritised the economy at the expense of protecting human life, and by implication have demonstrated an ideological leadership paradigm that prioritises the economy over the preservation of human life. This paradigm of ‘economic priority’ fails to realise that there is no economy without humans in the first place. This ideological framework is bound to capitalism and further perpetuates individual self-interest. Other global leaders have demonstrated positive responses that attempt to protect human life at all costs, above the wellbeing of economy. These leaders now nervously await vaccines, fear a potential ‘second wave’ of infections, and anxiously try to discern what their nations will become after the pandemic.

South Africa experienced a similarly uncertain period between 1990-1994. During a turbulent time of social and economic rebuilding, President-to-be Nelson Mandela led with the philosophy of Ubuntu. Mark Malisa and Michelle McAnuff-Gumbs explain this as they attempt to grasp Mandela’s vision in the edited volume The Individual and Utopia: A Multidisciplinary Study of Humanity and Perfection. They write: “Instead of recreating or crafting a policy of vengeance for the crimes of apartheid, Mandela used the philosophy of Ubuntu and masakhane to invite all South Africans to help rebuilding South Africa.” Masakhane, which means “let us build together,” is a paradigm that is connected to Ubuntu. It transcends capitalist ideals that are solely focused on the individual, by working towards a utilisation of resources for the benefit of the whole community. Such a leadership framework is embedded in an ideology that is concerned with the development and improvement of human life. This principle is then practically demonstrated by economic policies that improve the human community through redistributing wealth.

African leaders can no longer utilise their leadership positions in the state for their own political agenda and individual interest. Rather, an Ubuntu leadership framework provokes a representative model for leaders to serve only in the interest of the entire human community in Africa. A redistribution of wealth from a paradigm of Ubuntu requires an ideological framework that is concerned about the community and is evaluated as such. For Ntibagiriwa, a human-conscious paradigm of Ubuntu and a value-driven model for economic growth require three actors, “the state, the market, and the people.” These three spheres will only be fully realised if the economic system prioritises the value of the human life.

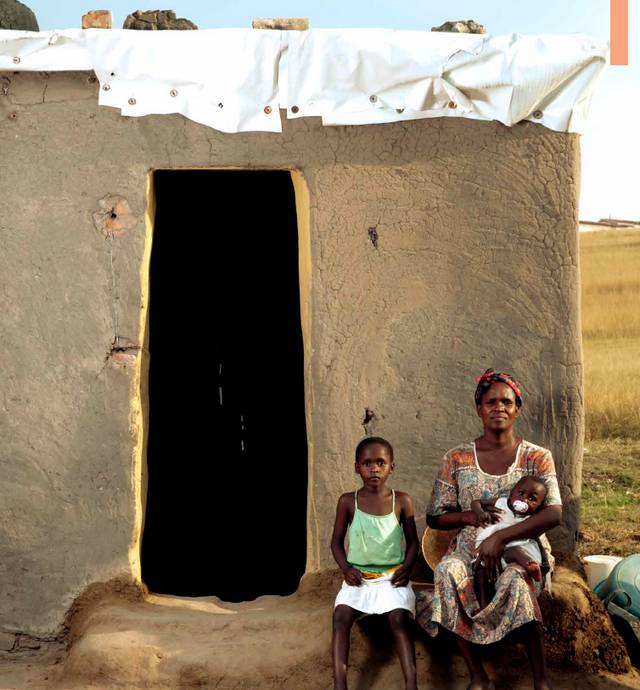

The transformation of infrastructure also applies to the improvement of medical facilities and access to health services. If a person exists through others, then the quality of medical treatment should not be determined by whether a person has medical aid. Public medical facilities cannot be inadequate or filled with outdated equipment. Health must be a right that is given to all people. Quality healthcare reflects the belief that the life of each human being is valuable and imbued with dignity. This truth can provide a starting point for a collective effort by African leaders to improve the African health sector, ensuring health and well-being for all citizens. Furthermore, medical research must incorporate all cultural (or indigenous) medicines within the sphere of human health. African indigenous medicines should not be seen as a negative, unscientific taboo. Medicine must embrace its very diverse scientific context in Africa by researching and evaluating all indigenous treatments. Higher education and government institutions must create research centres for African medicines. In an Ubuntu framework, institutions can no longer view themselves as individual entities concerned with securing profits and maintaining their statistical figures. All organisations must work together in a holistic, cohesive effort to liberate and develop Africa.

Building an economy with Ubuntu

The organisation of society should be based on the objective of ensuring that all people in each African state reach their full potential. The economic function of this organisational system prioritises development through education, agriculture, and industrialisation. Education cannot be limited to a one-dimensional form of learning. People in African states are not monolithic entities: human beings are dynamic and diverse. The establishment of variant ways of learning cultivates different skills within states, which allows for people’s development to benefit the continent’s economy. Learning can be conducted online and readapted to nurture people’s skills through African- centred approaches to education. Education in Africa must also encompass a focus on agricultural development within rural areas, and result in the implementation of artisan schools to develop diverse skillsets.

In terms of agriculture, a cohesive effort through the use of technology is in the continent’s interest. Workshops and programs can be offered to farmers online, which can assist them in addressing drought and animal care, for instance. This is possible if education in rural areas includes the skills of using the internet and gives potential farmers the practical skills needed from the high school level. Prioritising agricultural development results in Africa’s food being produced by the continent itself. It allows the people to be active participants in the shared food that people consume in their various communities. The agrarian community are active participants in the economic market of each country, which provides an opportunity for trade between African countries. This eliminates the divide between the urban and rural areas in economic participation. This economic market is designed to favour not only the people of an individual country, but all states on the continent. The industrialisation of agriculture should also promote creativity in clothing manufacturing through animal resources, and ought to evoke African leaders to work together to utilise other mineral and water resources in a cohesive effort to liberate Africa from non-African countries. This use of technology would not only benefit certain individuals and corporations, but rather equitably benefit people within all the ‘states’ of Africa. Economic development is thus achieved by each state creating a market that transforms existing institutions to be focused on human well-being, and inventing new systems and skills that will benefit citizens.

Ensuring accountability from leaders

People’s welfare is thus an imperative for an Ubuntudriven leadership paradigm to be initiated in each state, and this clear people-centred leadership allows for a transparent and accountable system of governance. Technology can facilitate this at multiple levels. Online platforms can allow citizens to track tenders for infrastructural projects and assist in monitoring the progress of developments by uploading photos and videos, ensuring that services have been successfully delivered. The meeting of basic needs can also be verified through the government’s website: citizens could apply for housing, for improvements to their homes, and also submit their applications and complaints. Technology can thus enable us to monitor our leaders’ service delivery and vote accordingly. Voters should receive annual reports of progress that are submitted by the elected leaders in office. This requires that each citizen has access to internet-connected devices, and a commitment from all levels of government.

Turning towards Ubuntu after COVID-19 is an opportunity for us all to participate in the creation of a market that desires “to grow together” (Masakhane). This ‘industrial resolution’ is a call towards a collective commitment that encourages institutions to rethink their economic policies and priorities, in order to benefit all African communities. It works towards the ideal of a united African state, where leaders cohesively prioritise the quality of life for each citizen: a truly Ubuntu leadership paradigm that develops the continent and paves the way for Africa’s economic liberation.