Alumni on the Move

A case study in COMPLEXITY: The pandemic and the power of systems thinking

Holistic, integrated, systemic: these words are bandied about so frequently that they can easily become meaningless jargon. Jai Clifford-Holmes (South Africa & RU, 2011) revisits key concepts and reminds us of the power of systems thinking to illuminate complex problems.

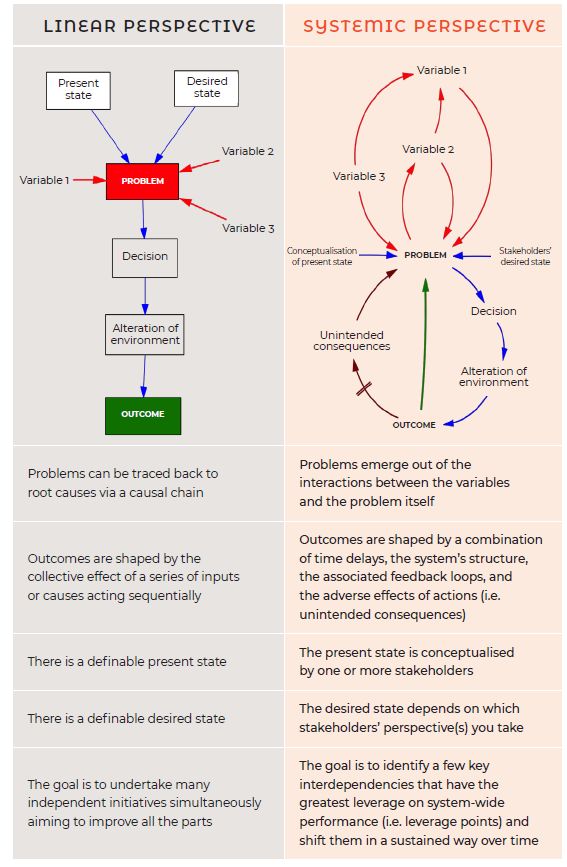

Much ink has been spilt trying to define what “systems thinking” is and what is involved in using “a systems approach”. Part of the difficulty is that systems themselves are characterised by multiple things happening at once, whereas words must necessarily follow one after the other. To work with systems we need to mirror the phenomena of interest, which is why systems diagrams and models are a core part of most systemic approaches. Systems thinking is most useful when tackling concrete, complex cases while drawing from a set of concepts, tools and approaches that are informed by a systemic paradigm, or way of seeing the world. The Covid-19 pandemic provides an opportunity for applying a systemic approach to a complex case that needs little introduction. A second case study explores the conflicts over Africa’s largest dam within a complex transboundary catchment, namely the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam on the Nile River

If you’re new to systems thinking (or a little rusty), the sidebars alongside this text contain the key concepts.

Where did Covid-19 come from? Busting the myth of the “unforeseen crisis”

From disastrous wildfires in Australia to locust hordes in East Africa, the kick-off to the new decade posed multiple challenges even before Covid-19 was declared a global pandemic. As a species, we tend to think and plan with the assumption that our tomorrows are likely to be similar to our todays. We are allergic to deep uncertainty and surprised by “unforeseen disasters”. Disasters that emerge out of the realm of “unknown unknowns” (i.e. when we don’t know what we don’t know) are often called Black Swan events. But is the Covid-19 pandemic actually a Black Swan?

As leading epidemiologist Larry Brilliant has said: “The whole epidemiological community has been warning everybody for the past 10 or 15 years that it wasn’t a question of whether we were going to have a pandemic like this. It was simply when.” A 2014 report by Bank of America stated that the risk of a global pandemic had never been higher. An estimate in 2014 by the World Travel & Tourism Council put the cost of a global pandemic, including the knock-on impacts, to be around $3.5 trillion. In 2020, the estimates are about three times that.

For Nassim Taleb, the philosopher, risk analyst and author of The Black Swan, Covid-19 is the furthest thing from a Black Swan. In late January 2020, when the virus was still mainly confined to China, Taleb published a paper through the New England Complex Systems Institute with two colleagues. The authors argued that the combination of increased global connectivity and the particular properties of the coronavirus meant that exponential spread was highly likely (unless extremely assertive action was taken at a global level). This projection was made without a highly sophisticated epidemiological model (as Taleb has put it elsewhere, you do not need advanced analytics to work out whether to get out of the way of the path of an oncoming avalanche).

A systems approach to Covid-19

The rapid spread and disastrous effects of the Covid-19 pandemic demonstrate several key systems concepts in action. The spread of the virus is the result of multiple interacting delays, non-linearity, and reinforcing feedback loops. Like Aids, Ebola and the Zika virus, Covid-19 belongs to the family of zoonotic diseases. These diseases originate in animal populations under severe environmental pressure from deforestation and intensive agriculture and then leap to human populations. For millions of people living in persistent poverty, bushmeat is a reliable source of protein. Zoonotic diseases are thus given plenty of opportunities to spread from animal to human hosts and then from community to community, city to city and country to country via our increasingly connected world.

The spread of the virus happens through a reinforcing feedback effect in which the more infected people there are, the more viral carriers there are, the higher the infection rate, the greater the number of people infected, and so on. Given that the Covid-19 virus can be spread before any recognisable symptoms manifest, the reinforcing feedback effect ensures rapid spread. Meanwhile, key components of testing kits and most personal protection equipment (PPE) are subject to global supply chains that result in delays in getting the quantities of PPE and testing kits to where they are required. There are further delays in the flow of information (between testing being rolled-out, through to analysing tests, processing results, communicating the results to decision makers and then acting on decisions). Hence our ability to respond to increasing infections is constrained by multiple interacting delays in material and information flows. Infection rates therefore rise exponentially faster than our ability to respond to the infections. Hence the relationship between the spread of the virus and our responses to it are non-linear: if we respond aggressively at an early stage, we can stem the spread of the virus with relative ease; if we wait till the virus has evidently spread through our population, our responses need to be dramatic, far-reaching and costly. This is, in many respects, commonplace wisdom. Many of us were brought up with phrases like ‘a stitch in time saves nine’ and ‘an ounce of prevention is equal to a pound of cure’. By not intervening pro-actively at an earlier stage, the cost of dealing with the pandemic has soared from tens of millions to trillions.

Seeing systems

People often have a problem ‘seeing’ systems, even in the case of an ‘obviously’ systemic problem like the COVID-19 pandemic. It takes work to acquire the basic building blocks of systems theory and it takes work to lead and manage with a systemic perspective. On the other hand, failure to understand system dynamics can lead us into cycles of blaming and defensiveness: the enemy is always out there, and problems are always caused by someone else – Donald Trump’s attempt to blame China for the Covid-19 pandemic is a classic example. A systemic perspective and a systems toolkit are not solutions in and of themselves, but rather a paradigm with an interconnected set of concepts and approaches that can be useful in an interconnected, uncertain world. This paradigm is a particularly useful tool for leaders and decisionmakers. For a further case study on using systems theory in the African context – the conflicts over the Great Ethiopian Renaissance Dam on the Nile River – see below.

Cheat sheet for leaders and managers:

A no-computers-required process for implementing a systems approach in a problem context*

-

Build a strong foundation for change by engaging multiple stakeholders to identify an initial vision and picture of current reality.

-

Engage stakeholders to explain their often-competing views of why a chronic, complex problem persists despite people’s best efforts to solve it.

-

Integrate the diverse perspectives into a map/model/diagram that provides a more complete picture of the system and interconnected causes of the problem.

-

Support stakeholders to see how their well-intended efforts to solve the problem often make it worse.

-

Commit to a compelling vision of the future and supportive strategies that can lead to system-wide change.

*Adapted from: Stroh, D. P., & Zurcher, K. (2012). Acting and Thinking Systemically. The Systems Thinker, 23(6), pp. 2–7.